Pictured is Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence's Chief Medical Officer and one of the authors of the poster presentation: Bonnie Weiner, MD, MSEC, MBA.

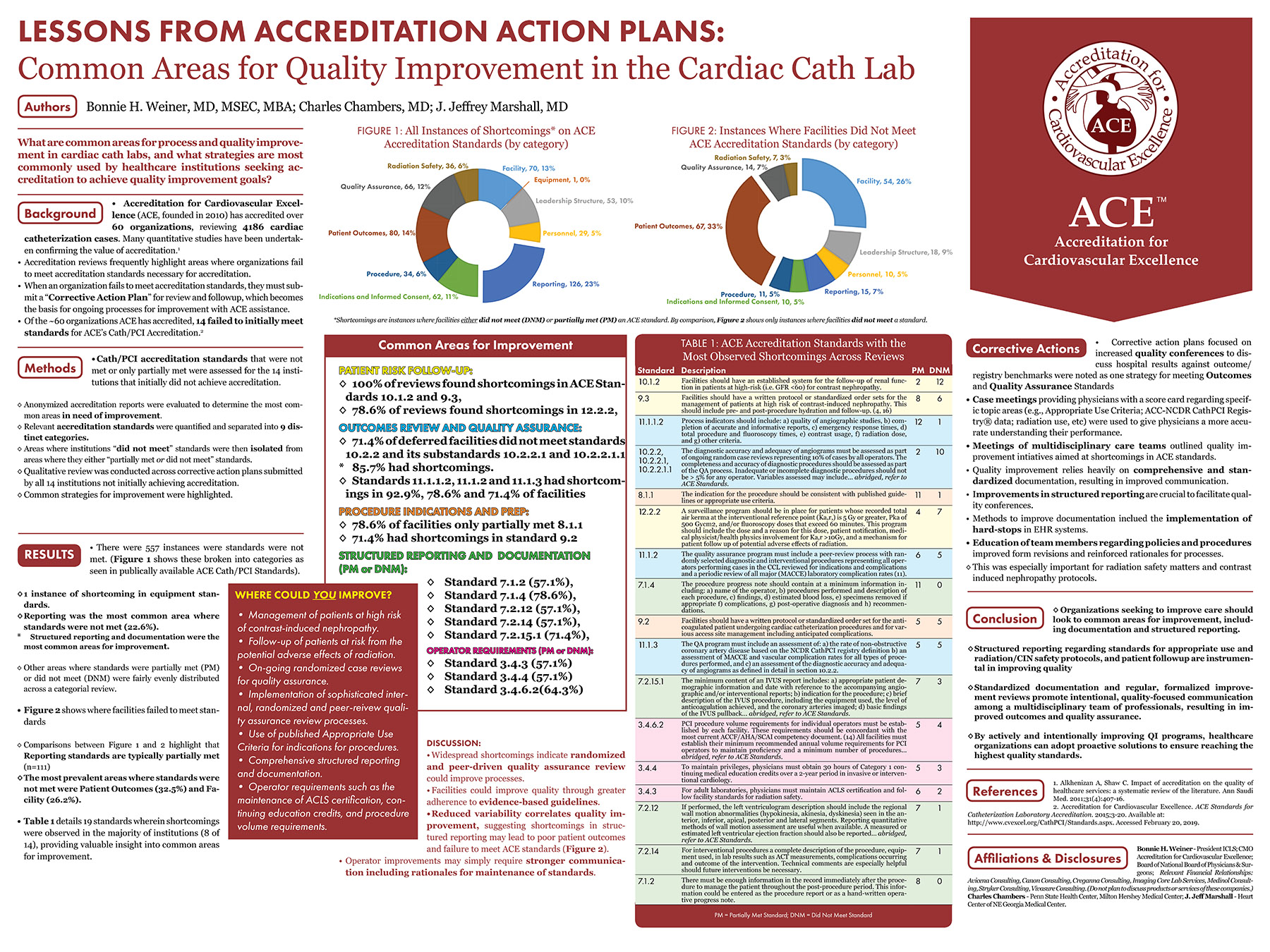

Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence was awarded 3rd place in the American College of Cardiology's 2019 Quality Summit poster competition. Our poster focused on the common elements of Quality Improvement & Corrective Action Plans for institutions seeking ACE accreditation. The poster analyzed what methods for improvement were most prevalent, and most successful at institutions achieving ACE accreditation, weighing these methods against the relevant specific ACE accreditation Standards.

View the Poster as a PDF

View the Poster as a PDF

Lessons from Accreditation Action Plans: Common Areas for Quality Improvement in the Cardiac Cath Lab

Authors: Bonnie H. Weiner, MD, MSEC, MBA; Charles Chambers, MD; J. Jeffrey Marshall, MD

What are common areas for process and quality improvement in cardiac cath labs, and what strategies are most commonly used by healthcare institutions seeking accreditation to achieve quality improvement goals?

Background

- Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence (ACE, founded in 2010) has accredited over 60 organizations, reviewing 4186 cardiac catheterization cases. Many quantitative studies have been undertaken confirming the value of accreditation.1

- Accreditation reviews frequently highlight areas where organizations fail to meet accreditation standards necessary for accreditation.

- When an organization fails to meet accreditation standards, they must submit a “Corrective Action Plan” for review and followup, which becomes the basis for ongoing processes for improvement with ACE assistance.

- Of the ~60 organizations ACE has accredited, 14 failed to initially meet standards for ACE’s Cath/PCI Accreditation.

Methods

- Cath/PCI accreditation standards that were not met or only partially met were assessed for the 14 institutions that initially did not achieve accreditation.

- Anonymized accreditation reports were evaluated to determine the most common areas in need of improvement.

- Relevant accreditation standards were quantified and separated into 9 distinct categories.

- Areas where institutions “did not meet” standards were then isolated from areas where they either “partially met or did not meet” standards.

- Qualitative review was conducted across corrective action plans submitted by all 14 institutions not initially achieving accreditation.

- Common strategies for improvement were highlighted.

Results

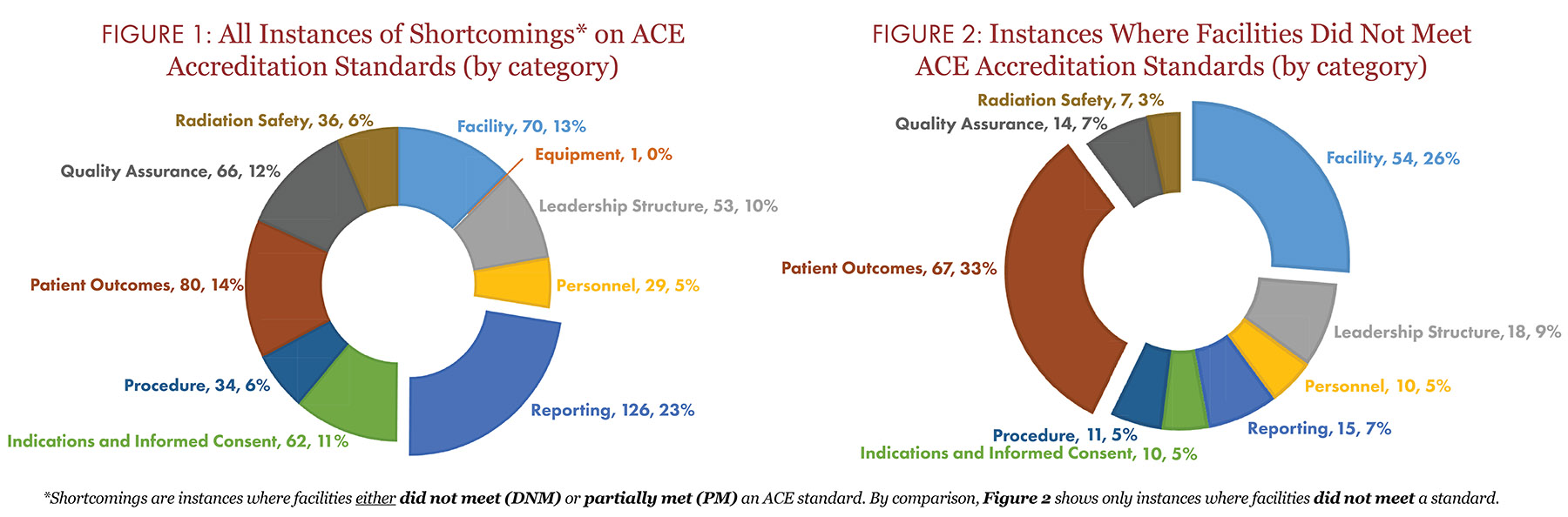

- There were 557 instances were standards were not met. (Figure 1 shows these broken into categories as seen in publically available ACE Cath/PCI Standards).

- 1 instance of shortcoming in equipment standards.

- Reporting was the most common area where standards were not met (22.6%).

- Structured reporting and documentation were the most common areas for improvement.

- Other areas where standards were partially met (PM) or did not meet (DNM) were fairly evenly distributed across a categorial review.

- Figure 2 shows where facilities failed to meet standards.

- Comparisons between Figure 1 and 2 highlight that Reporting standards are typically partially met (n=111)

- The most prevalent areas where standards were not met were Patient Outcomes (32.5%) and Facility (26.2%).

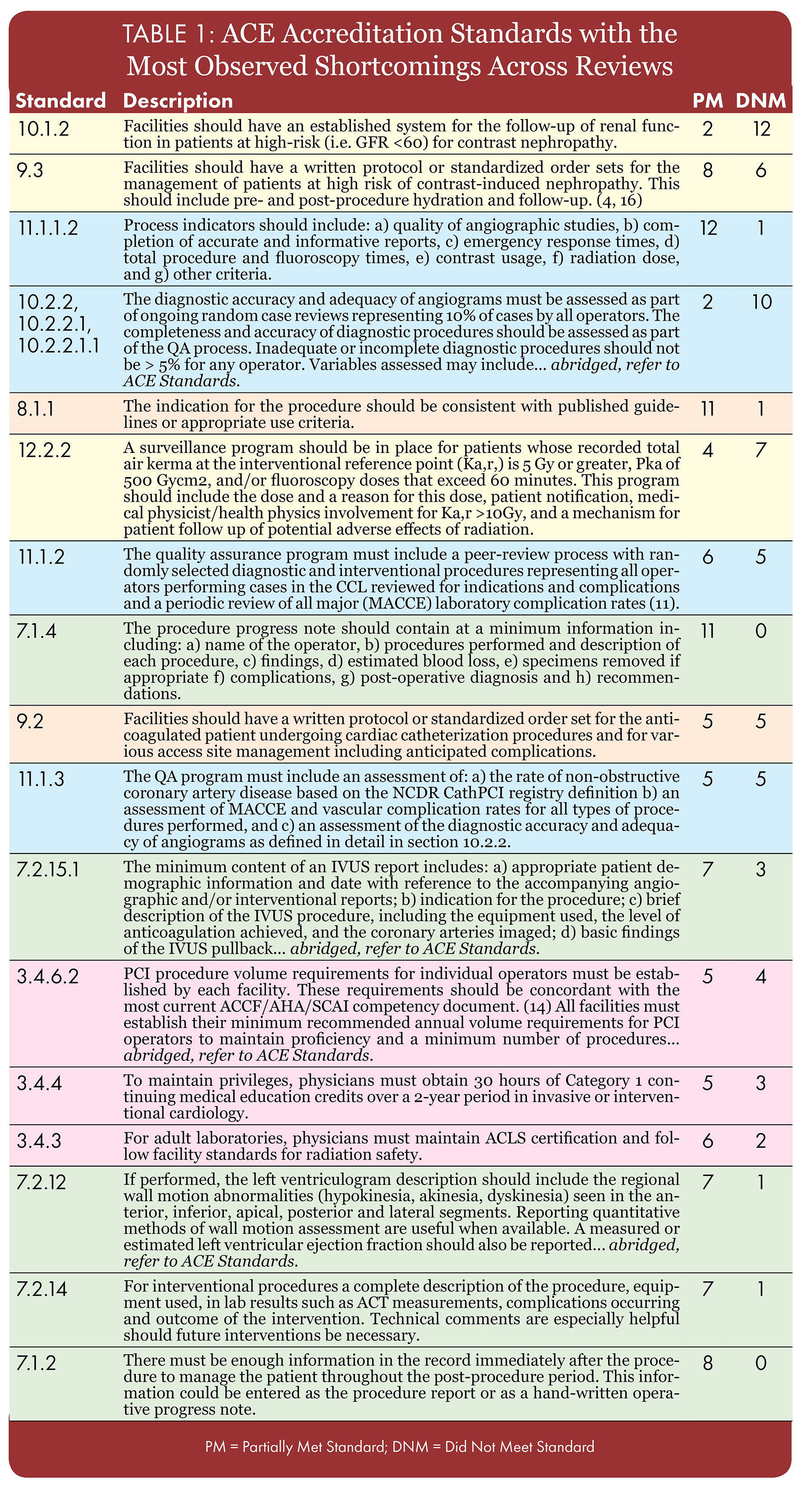

- Table 1 details 19 standards wherein shortcomings were observed in the majority of institutions (8 of 14), providing valuable insight into common areas for improvement.

Common Areas for Improvement

PATIENT RISK FOLLOW-UP:

- 100% of reviews found shortcomings in ACE Standards 10.1.2 and 9.3

- 78.6% of reviews found shortcomings in 12.2.2

OUTCOMES REVIEW AND QUALITY ASSURANCE:

- 71.4% of deferred facilities did not meet standards 10.2.2 and its substandards 10.2.2.1 and 10.2.2.1.1

- 85.7% had shortcomings.

- Standards 11.1.1.2, 11.1.2 and 11.1.3 had shortcomings in 92.9%, 78.6% and 71.4% of facilities

PROCEDURE INDICATIONS AND PREP:

- 78.6% of facilities only partially met 8.1.1

- 71.4% had shortcomings in standard 9.2

STRUCTURED REPORTING AND DOCUMENTATION (PM or DNM):

- Standard 7.1.2 (57.1%)

- Standard 7.1.4 (78.6%)

- Standard 7.2.12 (57.1%)

- Standard 7.2.14 (57.1%)

- Standard 7.2.15.1 (71.4%)

OPERATOR REQUIREMENTS (PM or DNM):

- Standard 3.4.3 (57.1%)

- Standard 3.4.4 (57.1%)

- Standard 3.4.6.2(64.3%)

Discussion

- Widespread shortcomings indicate randomized and peer-driven quality assurance review could improve processes.

- Facilities could improve quality through greater adherence to evidence-based guidelines.

- Reduced variability correlates quality improvement, suggesting shortcomings in structured reporting may lead to poor patient outcomes and failure to meet ACE standards (Figure 2).

- Operator improvements may simply require stronger communication including rationales for maintenance of standards.

Corrective Actions

- Corrective action plans focused on increased quality conferences to discuss hospital results against outcome/registry benchmarks were noted as one strategy for meeting Outcomes and Quality Assurance Standards

- Case meetings providing physicians with a score card regarding specific topic areas (e.g., Appropriate Use Criteria; ACC-NCDR CathPCI Registry® data; radiation use, etc) were used to give physicians a more accurate understanding their performance.

- Meetings of multidisciplinary care teams outlined quality improvement intiatives aimed at shortcomings in ACE standards.

- Quality improvement relies heavily on comprehensive and standardized documentation, resulting in improved communication.

- Improvements in structured reporting are crucial to facilitate quality conferences.

- Methods to improve documentation inclued the implementation of hard-stops in EHR systems.

- Education of team members regarding policies and procedures improved form revisions and reinforced rationales for processes.

- This was especially important for radiation safety matters and contrast induced nephropathy protocols.

Conclusion

- Organizations seeking to improve care should look to common areas for improvement, including documentation and structured reporting.

- Structured reporting regarding standards for appropriate use and radiation/CIN safety protocols, and patient followup are instrumental in improving quality

- Standardized documentation and regular, formalized improvement reviews promote intentional, quality-focused communication among a multidisciplinary team of professionals, resulting in improved outcomes and quality assurance.

- By actively and intentionally improving QI programs, healthcare organizations can adopt proactive solutions to ensure reaching the highest quality standards.

References

- Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(4):407-16.

- Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence. ACE Standards for Catheterization Laboratory Accreditation. 2015;3-20. Available at: http://www.cvexcel.org/CathPCI/Standards.aspx. Accessed February 20, 2019.

Affiliations & Disclosures

Bonnie H. Weiner - President ICLS; CMO Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence; Board of National Board of Physicians & Surgeons; Relevant Financial Relationships: Avicena Consulting, Canon Consulting, Creganna Consulting, Imaging Core Lab Services, Medinol Consulting, Stryker Consulting, Vivasure Consulting. (Do not plan to discuss products or services of these companies.) Charles Chambers - Penn State Health Center, Milton Hershey Medical Center; J. Jeff Marshall - Heart Center of NE Georgia Medical Center.